The Energy Crisis - Why Energy Democracy Will Help

Table of Contents

- Current Energy Crisis – Access & Generation

- Oil & Gas – Energy Bills Rising

- Renewable Energy Prices Falling

- Energy Disruption – Conflict & Extreme Weather

- Historical Arc of Energy Generation

- Moving Towards Energy Democracy

- Final Words

Current Energy Crisis – Access & Generation

The current energy crisis can be seen, at one level, as a conflict between energy access (which is largely democratised, at least for billions of people), and energy generation, which has relatively few providers.

The low volume of production companies suggests an opening for Energy Democracy. This refers to the concept in which energy generation and management is placed into the hands of the general population, creating a social ownership of energy.

To understand why democratising energy could help, we must first look at the growing global energy crisis.

Oil & Gas – Energy Bills Rising

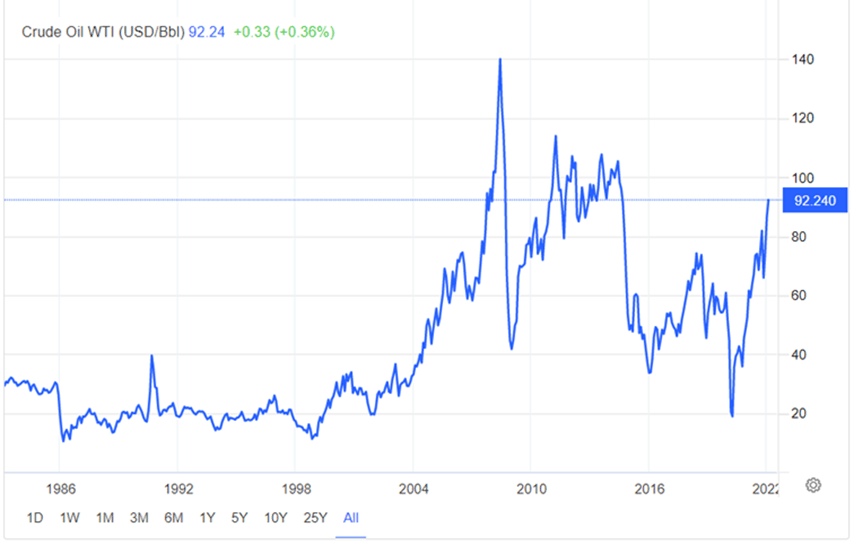

In recent years, and particularly since 2008, there have been an ongoing fuel crisis in the UK and the world at large. Oil prices rose increasingly dramatically from 2002 ($20/barrel) to 2008 ($147/barrel). There was some stability at around $100/barrel from 2012 to 2014, with additional smaller peaks in 2018 and 2021.

Image credit: tradingeconomics.com

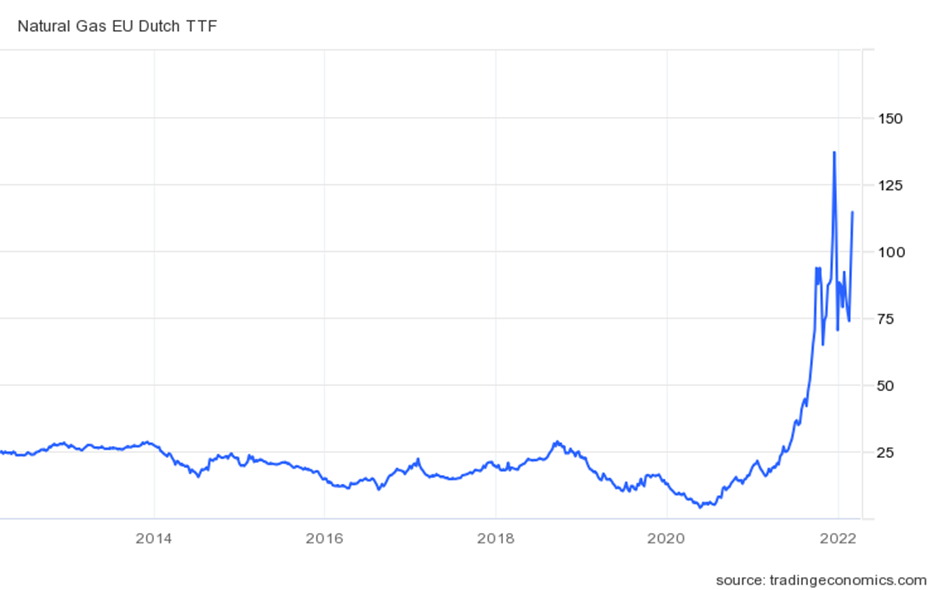

Again, a further crisis unravelled when gas prices in the EU and the UK rose from about €20/MWh in June 2021 to a peak of €175/MWh in late 2021, before falling to around €70/MWh at the time of writing.

Image credit: tradingeconomics.com

However, while the fossil fuel price rises, we can observe the cost of solar and wind power continuing to fall.

Renewable Energy Prices Falling

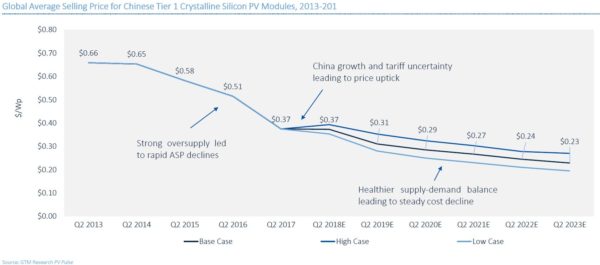

Currently solar will be about $0.29/W, which over a 20-year lifetime for a set of solar panels represents about $18/MWh, i.e., cheaper than the long-term gas prices over the past decade.

Similarly, Wind Energy averaged $51/MWh in 2019 and could be as low as $30/MWh, now in the same ball-park as the long-term average for gas.

Source: PV Magazine: The Path to $0.015/kWh Solar and Lower

Although clean energy is intermittent over short time periods, it delivers increasingly cheap, accessible and reliable energy over longer periods. This means that it is out-competing fossil fuels; delivering ownership to more people and increasing energy security.

Energy Disruption – Conflict & Extreme Weather

We can see how renewable energy provides greater security in the face of either energy conflicts or weather extremes.

For example, at least 3 major pipelines flow through Ukraine to European countries. Therefore, it is in Russia’s and Europe’s interest to maintain pipeline security and in Europe’s interest to reduce dependency. At the same time, it’s in Russia’s economic interests to maintain dependency, whilst reducing dependency on Ukraine.

Another consideration is how weather extremes in the UK, even in the past month, have led to power cuts. Distributed energy generation at every level increases energy security by allowing more graceful grid failure.

Historical Arc of Energy Generation

A crude analysis would suggest that, historically, energy production and use was local and distributed. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, energy production was derived from growing crops (solar, chemical); rivers driving mills; wind driving sailing ships or by burning wood or dung for heating and cooking.

In turn, energy storage took the form of human or animal energy storage and was used by putting both to work, which transfers solar and chemical energy to kinetic energy.

Therefore, to a first approximation, energy production and use was a de-facto human right and necessity.

The economics of the use of fossil fuels and the industrial revolution changed all of that, because it became possible to extract and use orders of magnitudes more power than manual labour. Consequently, higher development costs placed energy generation into fewer hands. In essence, mechanisation and the energy density of fossil fuels outpaced everything else.

On the other hand, the limitations of mechanisation in the Industrial Revolution led to the mass culture of the 20th century; while the introduction of personal, mechanised transport and electricity started to return energy access to the population.

Moving Towards Energy Democracy

As we enter the disruptive phase of decarbonisation, it’s becoming increasingly apparent that the centralised energy generation models designed for the 20th century are not suitable for the 21st.

This is clearly demonstrated when we consider both the trends towards increased electrification, such as Electric Vehicles, and the emerging markets for electricity, particularly in developing countries.

In the same way that computer technology since the 1980s and through into the 2020s has given a large proportion of the global population the opportunity (in theory) to communicate, broadcast and affect society globally, we should expect a similar process with regard to energy itself.

And we should expect it for similar reasons.

Computers have become ubiquitous, because the costs of suitable technology have come down to the degree that it has become accessible; the process for energy generation and storage are following a similar path.

This is partly because of the technology itself (e.g., mobile computing has galvanised R&D in battery technology), but also because of our growing awareness of the changes we need to make now to equip us in the decades to come.

This can be seen as a process of democratisation. That is, energy generation being placed increasingly in the hands of the general population.

Whether that’s at the individual, community, corporate, municipal or national level, this is starting to drive changes in society as profound as anything else over the past 40 years.

Final Words

Energy democratisation is arguably both the most likely outcome of energy shifts in the 21st century and the most desirable one. It would not only be beneficial from a social justice viewpoint, but also in alleviating the current energy crisis.

It’s also closer to the historical norm than the domination of energy generation by large-scale industry. Therefore, it is the most likely stable configuration from a viewpoint of energy security, given the increasingly erratic fuel crises and the need to respond to climate change in the 21st century.

Ultimately, it’s the easiest means by which the remainder of our global community can gain access to energy supplies.

As we lurch into another year of global tensions and tumult, it is likely it will only serve to fast-forward the process of democratising energy, in the same sense that the COVID-19 pandemic has also served to accelerate this technological transformation over the past 2 years.

Julian Skidmore is Versinetic’s EV Industry Analyst.

He has a Computer Science degree from UEA and an MPhil in Computer Architecture from Manchester University, as well as over 20 years of experience in embedded systems development.

As a senior software engineer, Julian has worked on EV charging and V2G projects, and has also co-authored EV-related articles for the electronics industry press.

Julian is a proponent of the zero-carbon society and a Guardian News ‘climate hero’. He has owned a battery EV for over two years, has investments in wind farm cooperatives, and has a 4KW domestic solar PV installation.